To get into the lab you push a sequence of buttons on a keypad. If you get the sequence right the door lets you in. If you don’t then it won’t. This is exactly the sort of task that our little computers are intended to perform. Let’s take a look at some of the technology that we would need.

We take for our model system a lock with 10 buttons that will unlock if the user presses the buttons ‘9’, ‘3’, ‘7’, ‘2’ in that order. Otherwise it will stay locked. As added sophistication it would be nice to flash a green LED when we unlock the door and flash a red LED if an incorrect sequence is entered.

This topic is covered in some detail in section 7.4.5 in the Computer book so I will not go into it here (though it might be a nice topic for a note of its own). All we need to move on here is a routine that we can call to read a keypad. I am going to assume, for the rest of this note, that we have a routine GetKey() that will use the algorithm from the book to wait till a key is pressed on the keypad and that will return a code identifying the key. Let us assume, for now, that our keypad has ten keys, labeled 1 through 10, and that GetKey returns an integer corresponding to the value on the key. Thus pressing the ‘1’ key will make GetKey return the value 1 (binary 0b00000001 or hex 0x01).

Everything here and in the chapter ignores one potential problem with real, physical, switches. They often suffer from contact so that pressing the key a single time could result in more than one GetKey event. The extra complexity is best dealt with in the GetKey routine so I will assume that our GetKey takes care of making sure that the switch is solidly pushed before returning so that we won’t get false key events from bounces.

The doorlock system has three apparent outputs, two LEDs and the lock itself. I assume that the actual lock mechanism is handled with a simple solenoid. That is a coil of wire surrounding a magnet arranged so that if a current flows in the coil then the magnet moves. This movement then disengages the lock. In that case the three outputs each look to the computer like singe digital output pins. Since the GetKey example in the book uses port B to talk to the keypad let’s make a decision that port A bit 0 (PTA0) will drive the green LED, port A bit (PTA1) the red LED, and port A bit 2 (PTA2) the lock solenoid.

Now we get to the heart of the problem. How do we recognize a specific sequence of key presses?

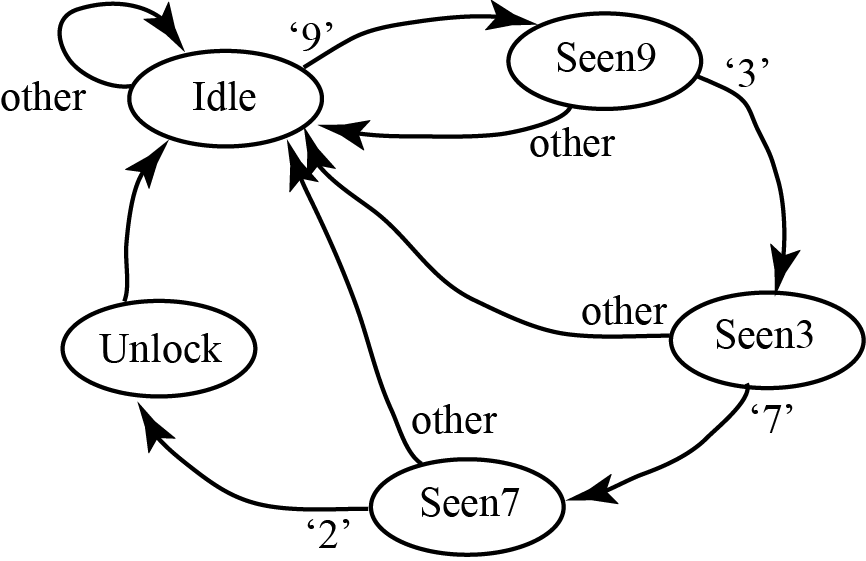

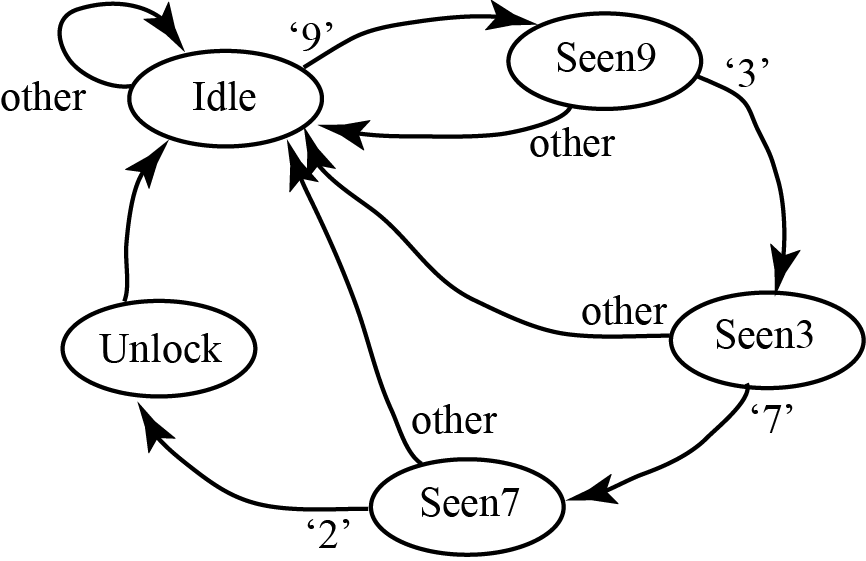

This is a classic case case for a finite state machine, like the ones discussed in the synchronous logic chapter of the electronics book. We start by creating a diagram of the states and the transitions that lead between them. What do we need in the way of states?

The normal state will have the machine sitting there waiting for a key press. Let’s call this state Idle.

We must do something if a key comes in. However, if we are Idle then the only thing that will change our state is seeing the first key, ‘9’. So if we see a ‘9’ then we move to a new state Seen9, otherwise we just go back to idle.

When we are in Seen9 we are waiting to see a ‘3’. Any key will change our state. A ‘3’ will take us to the new state Seen3 and anything else will take us back to Idle.

We handle Seen3 in much the same way. A ‘7’ will take us to new state Seen7 and anything else will take us back to Idle.

Similarly, in Seen7 a ‘2’ key will take us to a new state Unlock and anything else will take us back to Idle.

Lastly, if we are in the Unlock state then we turn on the green LED for a short time and turn on the unlock solenoid for several seconds to allow the use to open the door. In fact, the best interface would flash the green LED for the whole period when the door can be opened. After a few seconds the door should relock and the system return to idle.

We can draw this with a state diagram.

Here the arrows are labeled with the key values that cause the transition to be taken. I have used ’other as a shorthand for any key other than the correct one for that state. So, e.g., if we are in state Seen9 then other is any of ‘1’,‘2’,‘4’,‘5’,‘6’,‘7’, ‘8’, ‘9’, or ‘10’.

As it stands this will correctly handle the code recognition but we will need to work on the Unlock phase later on.

Inside our loop() routine we need to keep track of at least the current state. The usual way to do this is to number the states with consecutive integers and then use an integer variable to store the current state. In this case I will use the mapping

We can use the numbers directly or we can give names to make the code more readable. We could use regular ints for this or we could note that their values can never change and label as ‘const int’, like this:

const int Idle = 0

const int Seen9 = 1

const int Seen3 = 2

const int Seen7 = 3

const int Unlock = 4

and will need to define a current state variable, something like this

int CurrentState = Idle;

NOTE 1: I like to begin all of my global variable names with a capital letter and all of

my local variables with a lower case letter. This way I can tell at a glance whether a

variable is global or local.

NOTE 2: C/C++ likes to use int for any integer variable where we don’t particularly need to

think about the number of bits.

Within the loop we need code to handle each state. The most straightforward way to

handle this is with a set of if...else if ... clauses, like this:

void loop() {

if (Idle == currentState) {

// Do Idle stuff

} else if (Seen9 == currentState) {

// Do Seen9 stuff

} else if (Seen3 == currentState) {

// Do Seen3 stuff

} else if (Seen7 == currentState) {

// Do Seen7 stuff

} else if (Unlock == currentState) {

// Unlock the door

}

}

This is reasonably readable and very straightforward. However, C provides an even more

pleasing construct, the switch statement. The following is exactly equivalent but

a little easier to read.

void loop() {

switch (currentState) {

case Idle:

// Do Idle stuff

break;

case Seen9:

// Do Seen9 stuff

break;

case Seen3:

// Do Seen3 stuff

break;

case Seen7:

// Do Seen7 stuff

break;

case Unlock:

// Unlock the door

break;

} // End switch

} // End for

This is a common pattern and may be implemented more efficiently than the equivalent

if chain. It is worth learning but I will stick to the more familiar if chain for

the rest of this note.

At this point we have the skeleton of the state machine but it does not do anything. It can’t even change state yet. Now we need to start to fill in the states.

When we are idle we are waiting for a key to be pressed. That will only happen if we call GetKey() and then we will need to save the value that it returns. We will need a variable to hold the key and that variable will have to be declared in the usual way. There is no reason to use more than a character so we will use

char nextKey = -1;

where I have chosen to initialize it with an impossible value.

Now I can read the next key press with

nextKey = GetKey();

Then I need to look at the key. If it is a ‘9’ (represented by the simple value 0x09) then we need to change the state. Otherwise we do nothing. This gives us this fragment

if (Idle == currentState) {

nextKey = GetKey();

if (9 == nextKey) {

currentState = Seen9;

}

} else if (Seen9 == currentState) {

Here we see how to change state. We simply change the value of the currentState variable.

Next time round the loop when we examine currentState it will have the new value and

we will be in state Seen9.

This is very, very similar. Again, we wait for a key and examine it. The only difference is that we cannot stay in the Seen9 state. If we don’t find a ‘3’ then we need to go back to the Idle state.

} else if (Seen9 == currentState) {

nextKey = GetKey();

if (3 == nextKey) {

currentState = Seen3;

} else {

currentState = Idle;

}

} else if (Seen3 == currentState) {

So the code is very similar. The main difference is that we now change state in every case.

These are basically just copies of Seen9 with the active key changed like this

} else if (Seen3 == currentState) {

nextKey = GetKey();

if (7 == nextKey) {

currentState = Seen7;

} else {

currentState = Idle;

}

} else if (Seen7 == currentState) {

nextKey = GetKey();

if ('2 == nextKey) {

currentState = Unlock;

} else {

currentState = Idle;

}

} else if (Unlock == currentState) {

The most straightforward way to implement this is just to turn on the green LED and the solenoid for 10 seconds and then drop back to Idle like this

} else if (Unlock == currentState) {

digitalWrite(PTA0, HIGH); // green LED on

digitalWrite(PTA2, HIGH); // Unlock solenoid

delay(10000); // Give them 10 seconds to open the door

digitalWrite(PTA0, LOW); // LED off

digitalWrite(PTA2, LOW); // Relock door

currentState = Idle;

}

The only thing that we have not done with this is play with the red light.

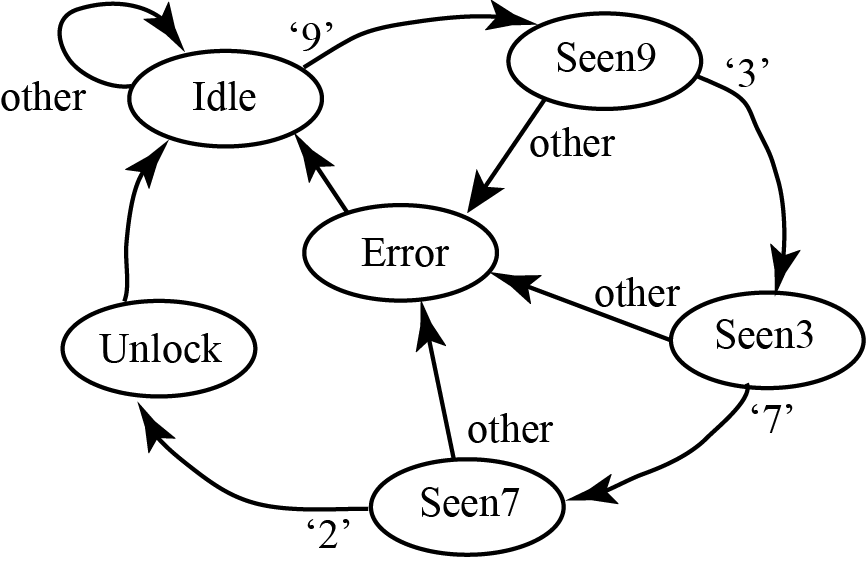

If we simply want the red LED to blink as soon as we recognize an invalid sequence then it is easy to add. The best way is to insert a new Error state to our diagram, like this:

This will mean adding an extra state to the mahine which is very straightforward. The state will need a number

#define Error 5

and then some handler code like this

} else if (Error == currentState) {

for (cycle = 0; cycle < 3; cycle++) {

digitalWrite(PTA1, HIGH); // Blink red LED three times

delay(300);

digitalWrite(PTA1, LOW); // LED off

delay(300);

}

currentState = Idle; // back to Idle

}

This uses a simple for loop to blink the red LED on and off three times in just under

2 seconds and then drops back to the Idle state.

Here is the resulting complete code with the variable declarations and the setup code.

const int Idle = 0

const int Seen9 = 1

const int Seen3 = 2

const int Seen7 = 3

const int Unlock = 4

int CurrentState = Idle; // Global runs state machine

void setup(void) {

//

// One-time setup

//

digitalWrite(PTA0, LOW); // Make sure LEDs and lock are off

digitalWrite(PTA1, LOW);

digitalWrite(PTA2, LOW);

pinMode(PTA0, OUTPUT); // Make outputs

pinMode(PTA1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(PTA2, OUTPUT);

portMode(PORTB, OUTPUT); // Needed by GetKey

}

//

// main loop

//

void looop() {

//

// Declare variables

//

char nextkey = -1; // Most recent key pressed

int cycle = 0; // Used to blink LED

if (Idle == currentState) { // Idle state

nextKey = GetKey();

if (9 == nextKey) {

currentState = Seen9;

}

} else if (Seen9 == currentState) { // Seen the '9' key

nextKey = GetKey();

if (3 == nextKey) {

currentState = Seen3;

} else {

currentState = Idle;

}

} else if (Seen3 == currentState) { // Seen '9', '3'

nextKey = GetKey();

if (7 == nextKey) {

currentState = Seen7;

} else {

currentState = Idle;

}

} else if (Seen7 == currentState) { // Seen '9', '3', '7'

nextKey = GetKey();

if ('2 == nextKey) {

currentState = Unlock;

} else {

currentState = Idle;

}

} else if (Unlock == currentState) { // Seen '9', '3', '7', '2'

digitalWrite(PTA0, HIGH); // green LED on

digitalWrite(PTA2, HIGH); // Unlock solenoid

delay(10000); // Give them 10 seconds to open the door

digitalWrite(PTA0, LOW); // LED off

digitalWrite(PTA2, LOW); // Relock door

currentState = Idle;

} else if (Error == currentState) { // Entered a wrong key

for (cycle = 0; cycle < 3; cycle++) {

digitalWrite(PTA1, HIGH); // Blink red LED three times

delay(300);

digitalWrite(PTA1, LOW); // LED off

delay(300);

}

currentState = Idle; // back to Idle

}

} // End for--Never leave here!

} // End main

This is a real working system, if a rather limited one. It has one serious problem. Because it signals an error as soon as a wrong key is pressed it is not all that hard to pick the lock by trying sequences and observing the red LED. It would be better if the lock accepted some number of invalid characters before generating a red LED. It would not be hard to implement this by adding some silent Error<n> states before the light flashing state.

It is also rather limited. The only way to alter the sequence of keys is by reprogramming the lock. A real lock would have to provide some means to alter the key sequence. The door lock on G025 can be programmed by and external laptop over some kind of interface. You can see the socket for the interface connector on the front of the lock. Our lock also only implements open-once behavior and does not support toggling the lock so that the door stays unlocked. I will let you think about how that might be implemented!